Satire is a

genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

of the

visual

The visual system comprises the sensory organ (the eye) and parts of the central nervous system (the retina containing photoreceptor cells, the optic nerve, the optic tract and the visual cortex) which gives organisms the sense of sight (the ...

,

literary

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

, and

performing art

The performing arts are arts such as music, dance, and drama which are performed for an audience. They are different from the visual arts, which are the use of paint, canvas or various materials to create physical or static art objects. Perfor ...

s, usually in the form of

fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary, or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with history, fact, or plausibility. In a traditi ...

and less frequently

non-fiction

Nonfiction, or non-fiction, is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to provide information (and sometimes opinions) grounded only in facts and real life, rather than in imagination. Nonfiction is often associated with be ...

, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or exposing the perceived flaws of individuals, corporations, government, or society itself into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive

social criticism

Social criticism is a form of academic or journalistic criticism focusing on social issues in contemporary society, in particular with respect to perceived injustices and power relations in general.

Social criticism of the Enlightenment

The orig ...

, using

wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society.

A feature of satire is strong

irony

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

or

sarcasm

Sarcasm is the caustic use of words, often in a humorous way, to mock someone or something. Sarcasm may employ ambivalence, although it is not necessarily ironic. Most noticeable in spoken word, sarcasm is mainly distinguished by the inflection ...

—"in satire, irony is militant", according to literary critic

Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye (July 14, 1912 – January 23, 1991) was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Frye gained international fame with his first book, '' Fearful Symmet ...

— but

parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

,

burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. ,

exaggeration

Exaggeration is the representation of something as more extreme or dramatic than it really is. Exaggeration may occur intentionally or unintentionally.

Exaggeration can be a rhetorical device or figure of speech. It may be used to evoke str ...

,

juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is an act or instance of placing two elements close together or side by side. This is often done in order to compare/contrast the two, to show similarities or differences, etc.

Speech

Juxtaposition in literary terms is the showing ...

, comparison, analogy, and

double entendre

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, of which one is typically obvious, whereas the other often conveys a message that would be too socially ...

are all frequently used in satirical speech and writing. This "militant" irony or sarcasm often professes to approve of (or at least accept as natural) the very things the satirist wishes to question.

Satire is found in many artistic forms of expression, including internet memes, literature, plays, commentary,

music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

,

film and television shows, and media such as lyrics.

Etymology and roots

The word ''satire'' comes from the

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

word ''satur'' and the subsequent phrase ''

lanx satura.'' ''Satur'' meant "full" but the juxtaposition with ''lanx'' shifted the meaning to "miscellany or medley": the expression ''lanx satura'' literally means "a full dish of various kinds of fruits".

[. However, the use of the word ''lanx'' in this phrase is disputed by B.L. Ullman]

Satura and Satire

(Class.Phil. 1913).

The word ''satura'' as used by

Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

, however, was used to denote only Roman verse satire, a strict genre that imposed

hexameter

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek and Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of syllables). It w ...

form, a narrower genre than what would be later intended as ''satire''.

Quintilian famously said that ''satura,'' that is a satire in hexameter verses, was a literary genre of wholly Roman origin (''satura tota nostra est''). He was aware of and commented on Greek satire, but at the time did not label it as such, although today the origin of satire is considered to be

Aristophanes' Old Comedy

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of hi ...

. The first critic to use the term "satire" in the modern broader sense was

Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern-day ...

.

To Quintilian, the satire was a strict literary form, but the term soon escaped from the original narrow definition. Robert Elliott writes:

The word ''satire'' derives from ''satura'', and its origin was not influenced by the

Greek mythological

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of d ...

figure of the ''

satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, :wikt:σάτυρος, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, :wikt:Σειληνός, σειληνός ), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears ...

''. In the 17th century, philologist

Isaac Casaubon

Isaac Casaubon (; ; 18 February 1559 – 1 July 1614) was a classical scholar and philologist, first in France and then later in England.

His son Méric Casaubon was also a classical scholar.

Life Early life

He was born in Geneva to two Fr ...

was the first to dispute the etymology of satire from satyr, contrary to the belief up to that time.

Humour

Laughter

Laughter is a pleasant physical reaction and emotion consisting usually of rhythmical, often audible contractions of the diaphragm and other parts of the respiratory system. It is a response to certain external or internal stimuli. Laughter ...

is not an essential component of satire; in fact there are types of satire that are not meant to be "funny" at all. Conversely, not all humour, even on such topics as politics, religion or art is necessarily "satirical", even when it uses the satirical tools of irony, parody, and

burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. .

Even light-hearted satire has a serious "after-taste": the organizers of the

Ig Nobel Prize

The Ig Nobel Prize ( ) is a satiric prize awarded annually since 1991 to celebrate ten unusual or trivial achievements in scientific research. Its aim is to "honor achievements that first make people laugh, and then make them think." The name of ...

describe this as "first make people laugh, and then make them think".

Social and psychological functions

Satire and

irony

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

in some cases have been regarded as the most effective source to understand a society, the oldest form of social study.

They provide the keenest insights into a group's

collective psyche, reveal its deepest values and tastes, and the society's structures of power.

Some authors have regarded satire as superior to non-comic and non-artistic disciplines like history or

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

.

In a prominent example from

ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, philosopher

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, when asked by a friend for a book to understand Athenian society, referred him to the plays of

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

.

Historically, satire has satisfied the popular

need

A need is dissatisfaction at a point of time and in a given context. Needs are distinguished from wants. In the case of a need, a deficiency causes a clear adverse outcome: a dysfunction or death. In other words, a need is something required for a ...

to

debunk

A debunker is a person or organization that exposes or discredits claims believed to be false, exaggerated, or pretentious. "to expose or excoriate (a claim, assertion, sentiment, etc.) as being pretentious, false, or exaggerated: to debunk adv ...

and

ridicule

Mockery or mocking is the act of insulting or making light of a person or other thing, sometimes merely by taunting, but often by making a caricature, purporting to engage in imitation in a way that highlights unflattering characteristics. Mocker ...

the leading figures in politics, economy, religion and other prominent realms of

power

Power most often refers to:

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

** Abusive power

Power may a ...

.

Satire confronts

public discourse

The public sphere (german: Öffentlichkeit) is an area in social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion influence political action. A "Public" is "of or concerning the ...

and the

collective imaginary, playing as a public opinion counterweight to power (be it political, economic, religious, symbolic, or otherwise), by challenging leaders and authorities. For instance, it forces administrations to clarify, amend or establish their policies. Satire's job is to expose problems and contradictions, and it's not obligated to solve them.

set in the history of satire a prominent example of a satirist role as confronting public discourse.

For its nature and social role, satire has enjoyed in many societies a special freedom license to mock prominent individuals and institutions.

The satiric impulse, and its ritualized expressions, carry out the function of resolving social tension.

Institutions like the

ritual clown

The Pueblo clowns (sometimes called sacred clowns) are jesters or tricksters in the Kachina religion (practiced by the Pueblo natives of the southwestern United States). It is a generic term, as there are a number of these figures in the ritua ...

s, by giving expression to the

antisocial tendencies

Antisocial behavior is a behavior that is defined as the violation of the rights of others by committing crime, such as stealing and physical attack in addition to other behaviors such as lying and manipulation. It is considered to be disrupti ...

, represent a

safety valve

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds ...

which re-establishes equilibrium and health in the

collective imaginary, which are jeopardized by the

repressive aspects of society.

The state of

political satire

Political satire is satire that specializes in gaining entertainment from politics; it has also been used with subversive intent where Political discourse analysis, political speech and dissent are forbidden by a regime, as a method of advancing ...

in a given society reflects the tolerance or intolerance that characterizes it,

and the state of

civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

and

human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

. Under

totalitarian regimes

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

any criticism of a political system, and especially satire, is suppressed. A typical example is the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

where the

dissidents

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

, such as

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

and

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for nu ...

were under strong pressure from the government. While satire of everyday life in the

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

was allowed, the most prominent satirist being

Arkady Raikin

Arkady Isaakovich Raikin (russian: Аркадий Исаакович Райкин; – 17 December 1987) was a Soviet stand-up comedian, theater and film actor, and stage director. He led the school of Soviet and Russian humorists for about hal ...

, political satire existed in the form of

anecdote

An anecdote is "a story with a point", such as to communicate an abstract idea about a person, place, or thing through the concrete details of a short narrative or to characterize by delineating a specific quirk or trait. Occasionally humorous ...

s that made fun of Soviet political leaders, especially

Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

, famous for his narrow-mindedness and love for awards and decorations.

Classifications

Satire is a diverse genre which is complex to classify and define, with a wide range of satiric "modes".

Horatian, Juvenalian, Menippean

Satirical literature can commonly be categorized as either Horatian, Juvenalian, or

Menippean.

Horacian

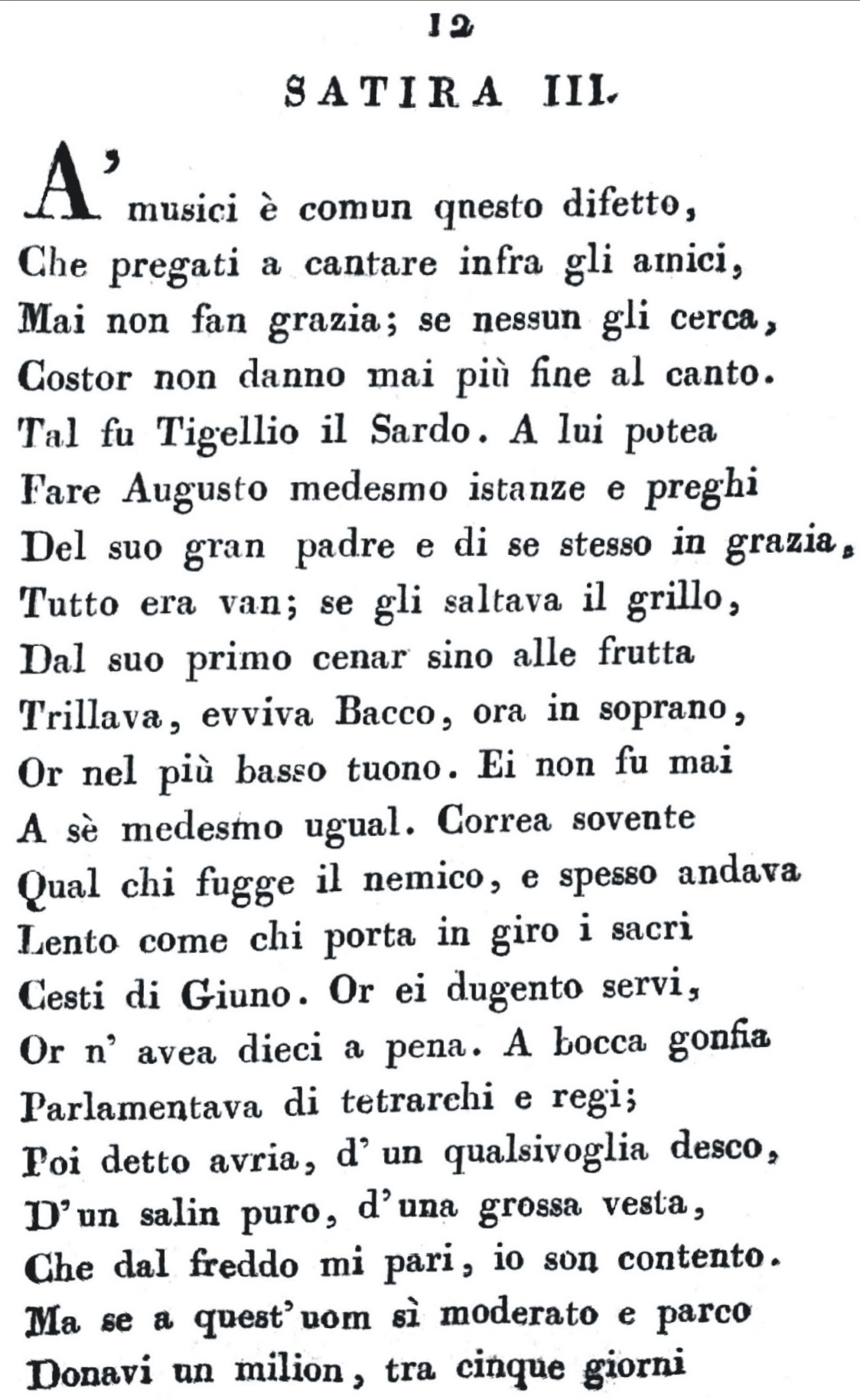

Horacian satire, named for the Roman satirist

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

(65–8 BCE), playfully criticizes some social vice through gentle, mild, and light-footed humour. Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus) wrote Satires to gently ridicule the dominant opinions and "philosophical beliefs of ancient Rome and Greece" (Rankin). Rather than writing in harsh or accusing tones, he addressed issues with humor and clever mockery. Horatian satire follows this same pattern of "gently

idiculingthe absurdities and follies of human beings" (Drury).

It directs wit, exaggeration, and self-deprecating humour toward what it identifies as folly, rather than evil. Horatian satire's sympathetic tone is common in modern society.

A Horacian satirist's goal is to heal the situation with smiles, rather than by anger. Horacian satire is a gentle reminder to take life less seriously and evokes a wry smile.

[ A Horatian satirist makes fun of general human folly rather than engaging in specific or personal attacks. Shamekia Thomas suggests, "In a work using Horatian satire, readers often laugh at the characters in the story who are the subject of mockery as well as themselves and society for behaving in those ways." ]Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

has been established as an author whose satire "heals with morals what it hurts with wit" (Green). Alexander Pope—and Horatian satire—attempt to teach.

Juvenalian

Juvenalian satire, named for the writings of the Roman satirist Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

(late first century – early second century AD), is more contemptuous and abrasive than the Horatian. Juvenal disagreed with the opinions of the public figures and institutions of the Republic and actively attacked them through his literature. "He utilized the satirical tools of exaggeration and parody to make his targets appear monstrous and incompetent" (Podzemny).Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

has been established as an author who "borrowed heavily from Juvenal's techniques in is critique

In linguistics, a copula (plural: copulas or copulae; abbreviated ) is a word or phrase that links the subject of a sentence to a subject complement, such as the word ''is'' in the sentence "The sky is blue" or the phrase ''was not being'' ...

of contemporary English society" (Podzemny).

Menippean

See Menippean satire

The genre of Menippean satire is a form of satire, usually in prose, that is characterized by attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities. It has been broadly described as a mixture of allegory, picaresque narrative, and ...

.

Satire versus teasing

In the history of theatre

The history of theatre charts the development of theatre over the past 2,500 years. While performative elements are present in every society, it is customary to acknowledge a distinction between theatre as an art form and entertainment and ''the ...

there has always been a conflict between engagement and disengagement on politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

and relevant issue, between satire and grotesque

Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ...

on one side, and jest

A joke is a display of humour in which words are used within a specific and well-defined narrative structure to make people laugh and is usually not meant to be interpreted literally. It usually takes the form of a story, often with dialogue, ...

with teasing

Teasing has multiple meanings and uses. In human interactions, teasing exists in three major forms: ''playful'', ''hurtful'', and ''educative''. Teasing can have a variety of effects, depending on how it is used and its intended effect. When teas ...

on the other.Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

defined the spectrum

A spectrum (plural ''spectra'' or ''spectrums'') is a condition that is not limited to a specific set of values but can vary, without gaps, across a continuum. The word was first used scientifically in optics to describe the rainbow of colors i ...

of satire in terms of "degrees of biting", as ranging from satire proper at the hot-end, and "kidding" at the violet-end; Eastman adopted the term kidding to denote what is just satirical in form, but is not really firing at the target. Nobel laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

satirical playwright Dario Fo

Dario Luigi Angelo Fo (; 24 March 1926 – 13 October 2016) was an Italian playwright, actor, theatre director, stage designer, songwriter, political campaigner for the Italian left wing and the recipient of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Literature. I ...

pointed out the difference between satire and teasing (''sfottò'').reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

side of the comic

a Media (communication), medium used to express ideas with images, often combined with text or other visual information. It typically the form of a sequence of Panel (comics), panels of images. Textual devices such as speech balloons, Glo ...

; it limits itself to a shallow parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

of physical appearance. The side-effect of teasing is that it humanizes and draws sympathy for the powerful individual towards which it is directed. Satire instead uses the comic to go against power and its oppressions, has a subversive

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. Sub ...

character, and a moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. A ...

dimension which draws judgement against its targets.operational

An operational definition specifies concrete, replicable procedures designed to represent a construct. In the words of American psychologist S.S. Stevens (1935), "An operation is the performance which we execute in order to make known a concept." F ...

criterion to tell real satire from ''sfottò'', saying that real satire arouses an outraged and violent reaction, and that the more they try to stop you, the better is the job you are doing. Fo contends that, historically, people in positions of power have welcomed and encouraged good-humoured buffoonery, while modern day people in positions of power have tried to censor, ostracize and repress satire.buffoonery

A jester, court jester, fool or joker was a member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch employed to entertain guests during the medieval and Renaissance eras. Jesters were also itinerant performers who entertained common folk at fairs and ...

, a form of comedy without satire's subversive edge. Teasing includes light and affectionate parody, good-humoured mockery, simple one-dimensional poking fun, and benign spoofs. Teasing typically consists of an impersonation

An impersonator is someone who imitates or copies the behavior or actions of another. There are many reasons for impersonating someone:

*Entertainment: An entertainer impersonates a celebrity, generally for entertainment, and makes fun of ...

of someone monkeying around with his exterior attributes, tic

A tic is a sudden, repetitive, nonrhythmic motor movement or vocalization involving discrete muscle groups.American Psychiatric Association (2000)DSM-IV-TR: Tourette's Disorder.''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders'', 4th ed., ...

s, physical blemishes, voice and mannerisms, quirks, way of dressing and walking, and/or the phrases he typically repeats. By contrast, teasing never touches on the core issue, never makes a serious criticism judging the target with irony

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

; it never harms the target's conduct, ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

and position of power; it never undermines the perception of his morality and cultural dimension.Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

propagated jest

A joke is a display of humour in which words are used within a specific and well-defined narrative structure to make people laugh and is usually not meant to be interpreted literally. It usually takes the form of a story, often with dialogue, ...

s and jokes against himself, with the aim of humanizing his image.

Classifications by topics

Types of satire can also be classified according to the topics it deals with. From the earliest times, at least since the plays of Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

, the primary topics of literary satire have been politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

, religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

and sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones ( ova, of ...

.taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

.clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

is a type of political satire

Political satire is satire that specializes in gaining entertainment from politics; it has also been used with subversive intent where Political discourse analysis, political speech and dissent are forbidden by a regime, as a method of advancing ...

, while religious satire

Religious satire is a form of satire that refers to religious beliefs and can take the form of texts, plays, films, and parody. From the earliest times, at least since the plays of Aristophanes, religion has been one of the three primary topics ...

is that which targets religious belief

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people often ...

s.blue comedy

Ribaldry or blue comedy is humorous entertainment that ranges from bordering on indelicacy to indecency. Blue comedy is also referred to as "bawdiness" or being "bawdy".

Sex is presented in ribald material more for the purpose of poking fun at ...

, off-color humor

Off-color humor (also known as vulgar humor, crude humor, or shock humor) is humor that deals with topics that may be considered to be in poor taste or vulgar. Many comedic genres (including jokes, prose, poems, black comedy, blue comedy, insult c ...

and dick joke

In comedy, a dick joke, penis joke, cock joke or knob joke is a joke that makes a direct or indirect reference to a human penis (known in slang parlance as a dick), also used as an umbrella term for dirty jokes. The famous quote from Mae West, "Is ...

s.

Scatology

In medicine and biology, scatology or coprology is the study of feces.

Scatological studies allow one to determine a wide range of biological information about a creature, including its diet (and thus where it has been), health and diseases s ...

has a long literary association with satire,grotesque

Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ...

, the grotesque body The grotesque body is a concept, or literary trope, put forward by Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin in his study of François Rabelais' work. The essential principle of grotesque realism is degradation, the lowering of all that is abstract, s ...

and the satiric grotesque.Shit

''Shit'' is a word considered to be vulgar and profane in Modern English. As a noun, it refers to fecal matter, and as a verb it means to defecate; in the plural ("the shits"), it means diarrhea. ''Shite'' is a common variant in British an ...

plays a fundamental role in satire because it symbolizes death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

, the turd being "the ultimate dead object".excrement

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

, exposes their "inherent inertness, corruption and dead-likeness".ritual clown

The Pueblo clowns (sometimes called sacred clowns) are jesters or tricksters in the Kachina religion (practiced by the Pueblo natives of the southwestern United States). It is a generic term, as there are a number of these figures in the ritua ...

s of clown societies Clown society is a term used in anthropology and sociology for an organization of comedic entertainers ( Heyoka or "clowns") who have a formalized role in a culture or society.

Description and function

Sometimes clown societies have a sacred role, ...

, like among the Pueblo Indians

The Puebloans or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Currently 100 pueblos are actively inhabited, among which Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zun ...

, have ceremonies with filth-eating.sin-eating

A sin-eater is a person who consumes a ritual meal in order to spiritually take on the sins of a deceased person. The food was believed to absorb the sins of a recently dead person, thus absolving the soul of the person. Sin-eaters, as a conse ...

is an apotropaic

Apotropaic magic (from Greek "to ward off") or protective magic is a type of magic intended to turn away harm or evil influences, as in deflecting misfortune or averting the evil eye. Apotropaic observances may also be practiced out of superst ...

rite in which the sin-eater (also called filth-eater), by ingesting the food provided, takes "upon himself the sins of the departed".black humor

Black comedy, also known as dark comedy, morbid humor, or gallows humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally considered serious or painful to discus ...

and gallows humor

Black comedy, also known as dark comedy, morbid humor, or gallows humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally considered serious or painful to discus ...

.

Another classification by topics is the distinction between political satire, religious satire and satire of manners.Comedy of manners

In English literature, the term comedy of manners (also anti-sentimental comedy) describes a genre of realistic, satirical comedy of the Restoration period (1660–1710) that questions and comments upon the manners and social conventions of a gre ...

, sometimes also called satire of manners, criticizes mode of life of common people; political satire aims at behavior, manners of politicians, and vices of political systems. Historically, comedy of manners, which first appeared in British theater in 1620, has uncritically accepted the social code of the upper classes.ridicule

Mockery or mocking is the act of insulting or making light of a person or other thing, sometimes merely by taunting, but often by making a caricature, purporting to engage in imitation in a way that highlights unflattering characteristics. Mocker ...

, irony

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

, sarcasm

Sarcasm is the caustic use of words, often in a humorous way, to mock someone or something. Sarcasm may employ ambivalence, although it is not necessarily ironic. Most noticeable in spoken word, sarcasm is mainly distinguished by the inflection ...

, cynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

, the sardonic

To be sardonic is to be disdainfully or cynically humorous, or scornfully mocking.

A form of wit or humour, being sardonic often involves expressing an uncomfortable truth in a clever and not necessarily malicious way, often with a degree of sk ...

and invective

Invective (from Middle English ''invectif'', or Old French and Late Latin ''invectus'') is abusive, reproachful, or venomous language used to express blame or censure; or, a form of rude expression or discourse intended to offend or hurt; vituperat ...

.ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

and folk forms, as well as in trickster

In mythology and the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story (god, goddess, spirit, human or anthropomorphisation) who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwi ...

tales and oral poetry

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Background

Oral poetry is ...

.cartoon strip

A comic strip is a sequence of drawings, often cartoons, arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions. Traditionally, throughout the 20th and into the 21st c ...

s, and graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

. Examples are Dada

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (Zurich), Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 192 ...

sculptures, Pop Art works, music of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

and Erik Satie

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie (, ; ; 17 May 18661 July 1925), who signed his name Erik Satie after 1884, was a French composer and pianist. He was the son of a French father and a British mother. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire, but was an und ...

, punk

Punk or punks may refer to:

Genres, subculture, and related aspects

* Punk rock, a music genre originating in the 1970s associated with various subgenres

* Punk subculture, a subculture associated with punk rock, or aspects of the subculture s ...

and rock music

Rock music is a broad genre of popular music that originated as " rock and roll" in the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s, developing into a range of different styles in the mid-1960s and later, particularly in the United States an ...

.media culture

In cultural studies, media culture refers to the current Western capitalist society that emerged and developed from the 20th century, under the influence of mass media. The term alludes to the overall impact and intellectual guidance exerted by t ...

, stand-up comedy

Stand-up comedy is a comedy, comedic performance to a live audience in which the performer addresses the audience directly from the stage. The performer is known as a comedian, a comic or a stand-up.

Stand-up comedy consists of One-line joke ...

is an enclave in which satire can be introduced into mass media

Mass media refers to a diverse array of media technologies that reach a large audience via mass communication. The technologies through which this communication takes place include a variety of outlets.

Broadcast media transmit information ...

, challenging mainstream discourse.Comedy roast

A roast is a form of humor in which a specific individual, a guest of honor, is subjected to jokes at their expense, intended to amuse the event's wider audience. Such events are intended to honor a specific individual in a unique way. In addition ...

s, mock festivals, and stand-up comedians in nightclubs and concerts are the modern forms of ancient satiric rituals.

Development

Ancient Egypt

One of the earliest examples of what might be called satire,

One of the earliest examples of what might be called satire, The Satire of the Trades

''The Satire of the Trades'', also called ''The Instruction of Dua-Kheti'', is a didactic work of ancient Egyptian literature. It takes the form of an instruction, composed by a scribe from Sile named Dua-Kheti for his son Pepi. The author is th ...

, is in Egyptian writing from the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. The text's apparent readers are students, tired of studying. It argues that their lot as scribes is not only useful, but far superior to that of the ordinary man. Scholars such as Helck think that the context was meant to be serious.

The Papyrus Anastasi I {{More footnotes, date=March 2017

Papyrus Anastasi I (officially designated papyrus British Museum 10247) is an ancient Egyptian papyrus containing a satirical text used for the training of scribes during the Ramesside Period (i.e. Nineteenth and ...

(late 2nd millennium BC) contains a satirical letter which first praises the virtues of its recipient, but then mocks the reader's meagre knowledge and achievements.

Ancient Greece

The Greeks had no word for what later would be called "satire", although the terms cynicism and parody were used. Modern critics call the Greek playwright Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

one of the best known early satirists: his plays are known for their critical political and societal commentary

Social commentary is the act of using rhetorical means to provide commentary on social, cultural, political, or economic issues in a society. This is often done with the idea of implementing or promoting change by informing the general populace ab ...

,political satire

Political satire is satire that specializes in gaining entertainment from politics; it has also been used with subversive intent where Political discourse analysis, political speech and dissent are forbidden by a regime, as a method of advancing ...

by which he criticized the powerful Cleon

Cleon (; grc-gre, Κλέων, ; died 422 BC) was an Athenian general during the Peloponnesian War. He was the first prominent representative of the commercial class in Athenian politics, although he was an aristocrat himself. He strongly advocate ...

(as in ''The Knights

''The Knights'' ( grc, Ἱππεῖς ''Hippeîs''; Attic: ) was the fourth play written by Aristophanes, who is considered the master of an ancient form of drama known as Old Comedy. The play is a satire on the social and political life of clas ...

''). He is also notable for the persecution he underwent.Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

. His early play ''Drunkenness'' contains an attack on the politician Callimedon

Callimedon ( grc, Καλλιμέδων) was an orator and politician at Classical Athens, Athens during the 4th century BCE who was a member of the Rise of Macedon, pro-Macedonian faction in the city. None of his speeches survive, but details of ...

.

The oldest form of satire still in use is the Menippean satire

The genre of Menippean satire is a form of satire, usually in prose, that is characterized by attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities. It has been broadly described as a mixture of allegory, picaresque narrative, and ...

by Menippus of Gadara. His own writings are lost. Examples from his admirers and imitators mix seriousness and mockery in dialogues and present parodies before a background of diatribe

A diatribe (from the Greek ''διατριβή''), also known less formally as rant, is a lengthy oration, though often reduced to writing, made in criticism of someone or something, often employing humor, sarcasm, and appeals to emotion.

His ...

. As in the case of Aristophanes plays, menippean satire turned upon images of filth and disease.

Ancient China

Satire, or fengci (諷刺) the way it's called in Chinese, goes back at least to Confucius

Confucius ( ; zh, s=, p=Kǒng Fūzǐ, "Master Kǒng"; or commonly zh, s=, p=Kǒngzǐ, labels=no; – ) was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. C ...

, being mentioned in the Book of Odes (Shijing 詩經). It meant “to criticize by means of an ode”. In the pre-Qin era it was also common for schools of thought to clarify their views through the use of short explanatory anecdotes, also called yuyan (寓言), translated as "entrusted words". These yuyan usually were brimming with satirical content. The Daoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the ''Tao'' ...

text Zhuangzi Zhuangzi may refer to:

* ''Zhuangzi'' (book) (莊子), an ancient Chinese collection of anecdotes and fables, one of the foundational texts of Daoism

**Zhuang Zhou

Zhuang Zhou (), commonly known as Zhuangzi (; ; literally "Master Zhuang"; als ...

is the first to define this concept of Yuyan. During the Qin and Han dynasty, however, the concept of yuyan mostly died out through their heavy persecution of dissent and literary circles. Especially by Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

and Han Wudi

Emperor Wu of Han (156 – 29 March 87BC), formally enshrined as Emperor Wu the Filial (), born Liu Che (劉徹) and courtesy name Tong (通), was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty of ancient China, ruling from 141 to 87 BC. His reign las ...

.

Roman world

The first Roman to discuss satire critically was Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

, who invented the term to describe the writings of Gaius Lucilius

Gaius Lucilius (180, 168 or 148 BC – 103 BC) was the earliest Roman satirist, of whose writings only fragments remain. A Roman citizen of the equestrian class, he was born at Suessa Aurunca in Campania, and was a member of the Scipion ...

. The two most prominent and influential ancient Roman satirists are Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

and Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

, who wrote during the early days of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. Other important satirists in ancient Latin are Gaius Lucilius and Persius. ''Satire'' in their work is much wider than in the modern sense of the word, including fantastic and highly coloured humorous writing with little or no real mocking intent. When Horace criticized Augustus, he used veiled ironic terms. In contrast, Pliny the Elder, Pliny reports that the 6th-century-BC poet Hipponax wrote ''satirae'' that were so cruel that the offended hanged themselves.

In the 2nd century AD, Lucian wrote ''True History'', a book satirizing the clearly unrealistic travelogues/adventures written by Ctesias, Iambulus, and Homer. He states that he was surprised they expected people to believe their lies, and stating that he, like them, has no actual knowledge or experience, but shall now tell lies as if he did. He goes on to describe a far more obviously extreme and unrealistic tale, involving interplanetary exploration, war among alien life forms, and life inside a 200 mile long whale back in the terrestrial ocean, all intended to make obvious the fallacies of books like ''Indica (Ctesias), Indica'' and ''The Odyssey''.

Medieval Islamic world

Medieval Arabic poetry included the satiric genre ''hija''. Satire was introduced into Arabic literature, Arabic prose literature by the author Al-Jahiz in the 9th century. While dealing with serious topics in what are now known as anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

, Sociology in medieval Islam, sociology and Psychology in medieval Islam, psychology, he introduced a satirical approach, "based on the premise that, however serious the subject under review, it could be made more interesting and thus achieve greater effect, if only one leavened the lump of solemnity by the insertion of a few amusing anecdotes or by the throwing out of some witty or paradoxical observations. He was well aware that, in treating of new themes in his prose works, he would have to employ a vocabulary of a nature more familiar in ''hija'', satirical poetry." For example, in one of his Zoology, zoological works, he satirized the preference for longer human penis size, writing: "If the length of the penis were a sign of honor, then the mule would belong to the (honorable tribe of) Quraysh (tribe), Quraysh". Another satirical story based on this preference was an ''One Thousand and One Nights, Arabian Nights'' tale called "Ali with the Large Member".

In the 10th century, the writer Tha'alibi recorded satirical poetry written by the Arabic poets As-Salami and Abu Dulaf, with As-Salami praising Abu Dulaf's Polymath, wide breadth of knowledge and then mocking his ability in all these subjects, and with Abu Dulaf responding back and satirizing As-Salami in return. An example of Arabic political satire included another 10th-century poet Jarir satirizing Farazdaq as "a transgressor of the Sharia" and later Arabic poets in turn using the term "Farazdaq-like" as a form of political satire.

The terms "comedy" and "satire" became synonymous after Aristotle's ''Poetics (Aristotle), Poetics'' was translated into Arabic language, Arabic in the Islamic Golden Age, medieval Islamic world, where it was elaborated upon by Early Islamic philosophy, Islamic philosophers and writers, such as Abu Bischr, his pupil Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Averroes. Due to cultural differences, they disassociated comedy from Greek dramatic representation and instead identified it with Arabic poetry, Arabic poetic themes and forms, such as ''hija'' (satirical poetry). They viewed comedy as simply the "art of reprehension", and made no reference to light and cheerful events, or troubled beginnings and happy endings, associated with classical Greek comedy. After the Latin translations of the 12th century, the term "comedy" thus gained a new semantic meaning in Medieval literature.

Ubayd Zakani introduced satire in Persian literature during the 14th century. His work is noted for its satire and obscene verses, often political or bawdy, and often cited in debates involving homosexual practices. He wrote the ''Resaleh-ye Delgosha'', as well as ''Akhlaq al-Ashraf'' ("Ethics of the Aristocracy") and the famous humorous fable ''Masnavi Mush-O-Gorbeh'' (Mouse and Cat), which was a political satire. His non-satirical serious classical verses have also been regarded as very well written, in league with the other great works of Persian literature. Between 1905 and 1911, Bibi Khatoon Astarabadi and other Iranian writers wrote notable satires.

Medieval Europe

In the Early Middle Ages, examples of satire were the songs by Goliards or Clerici vagantes, vagants now best known as an anthology called Carmina Burana and made famous as texts of a composition by the 20th-century composer Carl Orff. Satirical poetry is believed to have been popular, although little has survived. With the advent of the High Middle Ages and the birth of modern vernacular literature in the 12th century, it began to be used again, most notably by Chaucer. The disrespectful manner was considered "unchristian" and ignored, except for the moral satire, which mocked misbehaviour in Christian terms. Examples are ''Livre des Manières'' by (~1178), and some of Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales''. Sometimes Epic poetry, epic poetry (epos) was mocked, and even feudal society, but there was hardly a general interest in the genre.

In the High Middle Ages the work Reynard the Fox, written by Willem die Madoc maecte, and its translations were a popular work that satirized the class system at the time. Representing the various classes as certain anthropomorphic animals. As example, the lion in the story represents the nobility, which is portrayed as being weak and without character, but very greedy. Versions of Reynard the Fox were also popular well into the early modern period. The dutch translation Van den vos Reynaerde is considered a major medieval dutch literary work. In the dutch version De Vries argues that the animal characters represent barons who conspired against the Count of Flanders.

Early modern western satire

Direct social commentary via satire returned with a vengeance in the 16th century, when farcical texts such as the works of François Rabelais tackled more serious issues (and incurred the wrath of the crown as a result).

Two major satirists of Europe in the Renaissance were Giovanni Boccaccio and François Rabelais. Other examples of Renaissance satire include ''Till Eulenspiegel'', ''Reynard the Fox'', Sebastian Brant's ''Ship of Fools (satire), Narrenschiff'' (1494), Erasmus's ''Moriae Encomium'' (1509), Thomas More's ''Utopia (book), Utopia'' (1516), and ''Carajicomedia'' (1519).

The Elizabethan (i.e. 16th-century English) writers thought of satire as related to the notoriously rude, coarse and sharp satyr play. Elizabethan "satire" (typically in pamphlet form) therefore contains more straightforward abuse than subtle irony. The French Huguenot Isaac Casaubon

Isaac Casaubon (; ; 18 February 1559 – 1 July 1614) was a classical scholar and philologist, first in France and then later in England.

His son Méric Casaubon was also a classical scholar.

Life Early life

He was born in Geneva to two Fr ...

pointed out in 1605 that satire in the Roman fashion was something altogether more civilised. Casaubon discovered and published Quintilian's writing and presented the original meaning of the term (satira, not satyr), and the sense of wittiness (reflecting the "dishfull of fruits") became more important again. Seventeenth-century English satire once again aimed at the "amendment of vices" (Dryden).

In the 1590s a new wave of verse satire broke with the publication of Joseph Hall (bishop), Hall's ''Virgidemiarum'', six books of verse satires targeting everything from literary fads to corrupt noblemen. Although John Donne, Donne had already circulated satires in manuscript, Hall's was the first real attempt in English at verse satire on the Juvenalian model. The success of his work combined with a national mood of disillusion in the last years of Elizabeth's reign triggered an avalanche of satire—much of it less conscious of classical models than Hall's — until the fashion was brought to an abrupt stop by censorship.

Another satiric genre to emerge around this time was the satirical almanac, with François Rabelais's work ''Pantagrueline Prognostication'' (1532), which mocked astrological predictions. The strategies François utilized within this work were employed by later satirical almanacs, such as the ''Poor Robin'' series that spanned the 17th to 19th centuries.

Ancient and modern India

Satire (''Kataksh'' or ''Vyang'') has played a prominent role in Indian literature, Indian and Hindi literature, and is counted as one of the "Rasa (aesthetics), ras" of literature in ancient books. With the commencement of printing of books in local language in the nineteenth century and especially after India's freedom, this grew. Many of the works of Tulsi Das, Kabir, Munshi Premchand, village minstrels, Harikatha, Hari katha singers, poets, Dalit singers and current day stand up Indian comedians incorporate satire, usually ridiculing authoritarians, fundamentalists and incompetent people in power.

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment, an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries advocating rationality, produced a great revival of satire in Britain. This was fuelled by the rise of partisan politics, with the formalisation of the Tory and British Whig Party, Whig parties—and also, in 1714, by the formation of the Scriblerus Club, which included

The Age of Enlightenment, an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries advocating rationality, produced a great revival of satire in Britain. This was fuelled by the rise of partisan politics, with the formalisation of the Tory and British Whig Party, Whig parties—and also, in 1714, by the formation of the Scriblerus Club, which included Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

, John Gay, John Arbuthnot, Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, Robert Harley, Thomas Parnell, and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke. This club included several of the notable satirists of early-18th-century Britain. They focused their attention on Martinus Scriblerus, "an invented learned fool... whose work they attributed all that was tedious, narrow-minded, and pedantic in contemporary scholarship". In their hands astute and biting satire of institutions and individuals became a popular weapon. The turn to the 18th century was characterized by a switch from Horatian, soft, pseudo-satire, to biting "juvenal" satire.[Weinbrot, Howard D. (2007) ''Eighteenth-Century Satire: Essays on Text and Context from Dryden to Peter...']

p.136

/ref>

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

was one of the greatest of Anglo-Irish satirists, and one of the first to practise modern journalistic satire. For instance, In his ''A Modest Proposal'' Swift suggests that Irish peasants be encouraged to sell their own children as food for the rich, as a solution to the "problem" of poverty. His purpose is of course to attack indifference to the plight of the desperately poor. In his book ''Gulliver's Travels'' he writes about the flaws in human society in general and English society in particular. John Dryden wrote an influential essay entitled "A Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire" that helped fix the definition of satire in the literary world. His satirical ''Mac Flecknoe'' was written in response to a rivalry with Thomas Shadwell and eventually inspired Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

to write his satirical ''Dunciad''.

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

(b. May 21, 1688) was a satirist known for his Horatian satirist style and translation of the ''Iliad''. Famous throughout and after the Long eighteenth century, long 18th century, Pope died in 1744. Pope, in his ''The Rape of the Lock'', is delicately chiding society in a sly but polished voice by holding up a mirror to the follies and vanities of the upper class. Pope does not actively attack the self-important pomp of the British aristocracy, but rather presents it in such a way that gives the reader a new perspective from which to easily view the actions in the story as foolish and ridiculous. A mockery of the upper class, more delicate and lyrical than brutal, Pope nonetheless is able to effectively illuminate the moral degradation of society to the public. ''The Rape of the Lock'' assimilates the masterful qualities of a heroic epic, such as the ''Iliad'', which Pope was translating at the time of writing ''The Rape of the Lock''. However, Pope applied these qualities satirically to a seemingly petty egotistical elitist quarrel to prove his point wryly.

Other satirical works by Pope include the ''Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot''.

Daniel Defoe pursued a more journalistic type of satire, being famous for his ''The True-Born Englishman'' which mocks Xenophobia, xenophobic patriotism, and ''The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters''—advocating religious toleration by means of an ironical exaggeration of the highly intolerant attitudes of his time.

The pictorial satire of William Hogarth is a precursor to the development of political cartoons in 18th-century England.

Satire in Victorian England

Several satiric papers competed for the public's attention in the Victorian era (1837–1901) and Edwardian period, such as ''Punch (magazine), Punch'' (1841) and ''Fun (magazine), Fun'' (1861).

Perhaps the most enduring examples of Victorian satire, however, are to be found in the Savoy Operas of

Several satiric papers competed for the public's attention in the Victorian era (1837–1901) and Edwardian period, such as ''Punch (magazine), Punch'' (1841) and ''Fun (magazine), Fun'' (1861).

Perhaps the most enduring examples of Victorian satire, however, are to be found in the Savoy Operas of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

. In fact, in ''The Yeomen of the Guard'', a jester is given lines that paint a very neat picture of the method and purpose of the satirist, and might almost be taken as a statement of Gilbert's own intent:

:''"I can set a braggart quailing with a quip,''

:''The upstart I can wither with a whim;''

:''He may wear a merry laugh upon his lip,''

:''But his laughter has an echo that is grim!"''

Novelists such as Charles Dickens (1812-1870) often used passages of satiric writing in their treatment of social issues.

Continuing the tradition of Swiftian journalistic satire, Sidney Godolphin Osborne (1808-1889) was the most prominent writer of scathing "Letters to the Editor" of the London Times. Famous in his day, he is now all but forgotten. His maternal grandfather William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland was considered to be a possible candidate for the authorship of the Junius (writer), Junius letters. Osborne's satire was so bitter and biting that at one point he received a public censure from Parliament's then Home Secretary Sir James Graham, 3rd Duke of Montrose, James Graham. Osborne wrote mostly in the Juvenalian mode over a wide range of topics mostly centered on British government's and landlords' mistreatment of poor farm workers and field laborers. He bitterly opposed the New Poor Laws and was passionate on the subject of the British government's botched response to the Great Famine (Ireland), Great Irish Famine and the mistreatment of British Army, British soldiers during the Crimean War.

A number of works of fiction during this time, influenced by Egyptomania,

20th-century satire

Karl Kraus is considered the first major European satirist since Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

.[Knight, Charles A. (2004) ''Literature of Satire']

p.254

/ref> In 20th-century literature, satire was used by English authors such as Aldous Huxley (1930s) and George Orwell (1940s), which under the inspiration of Yevgeny Zamyatin, Zamyatin's Russian 1921 novel ''We (novel), We'', made serious and even frightening commentaries on the dangers of the sweeping social changes taking place throughout Europe. Anatoly Lunacharsky wrote ‘Satire attains its greatest significance when a newly evolving class creates an ideology considerably more advanced than that of the ruling class, but has not yet developed to the point where it can conquer it. Herein lies its truly great ability to triumph, its scorn for its adversary and its hidden fear of it. Herein lies its venom, its amazing energy of hate, and quite frequently, its grief, like a black frame around glittering images. Herein lie its contradictions, and its power.’ Many social critics of this same time in the United States, such as Dorothy Parker and H. L. Mencken, used satire as their main weapon, and Mencken in particular is noted for having said that "one horse-laugh is worth ten thousand syllogisms" in the persuasion of the public to accept a criticism. Novelist Sinclair Lewis was known for his satirical stories such as ''Main Street (novel), Main Street'' (1920), ''Babbitt (novel), Babbitt'' (1922), ''Elmer Gantry'' (1927; dedicated by Lewis to H. L. Menchen), and ''It Can't Happen Here'' (1935), and his books often explored and satirized contemporary American values. The film ''The Great Dictator'' (1940) by Charlie Chaplin is itself a parody of Adolf Hitler; Chaplin later declared that he would have not made the film if he had known about the Nazi concentration camps, concentration camps.[Chaplin (1964) ''My Autobiography'', p.392, quotation: ]

Modern Soviet Union, Soviet satire was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. This form of satire is recognized by its level of sophistication and intelligence used, along with its own level of parody. Since there is no longer the need of survival or revolution to write about, the modern Soviet satire is focused on the quality of life.

In the United States 1950s, satire was introduced into American

In the United States 1950s, satire was introduced into American stand-up comedy

Stand-up comedy is a comedy, comedic performance to a live audience in which the performer addresses the audience directly from the stage. The performer is known as a comedian, a comic or a stand-up.

Stand-up comedy consists of One-line joke ...

most prominently by Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl.taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

s and conventional wisdom of the time, were ostracized by the mass media establishment as ''sick comedians''. In the same period, Paul Krassner's magazine ''The Realist'' began publication, to become immensely popular during the 1960s and early 1970s among people in the Counterculture of the 1960s, counterculture; it had articles and cartoons that were savage, biting satires of politicians such as Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, the Vietnam War, the Cold War and the War on Drugs. This baton was also carried by the original National Lampoon (magazine), National Lampoon magazine, edited by Doug Kenney and Henry Beard and featuring blistering satire written by Michael O'Donoghue, P.J. O'Rourke, and Tony Hendra, among others. Prominent satiric stand-up comedian George Carlin acknowledged the influence ''The Realist'' had in his 1970s conversion to a satiric comedian.[Sullivan, James (2010) ''Seven Dirty Words: The Life and Crimes of George Carlin']

p.94

/ref>

A more humorous brand of satire enjoyed a renaissance in the UK in the early 1960s with the satire boom, led by comedians including Peter Cook, Alan Bennett, Jonathan Miller, and Dudley Moore, whose stage show ''Beyond the Fringe'' was a hit not only in Britain, but also in the United States. Other significant influences in 1960s British satire include David Frost, Eleanor Bron and the television program ''That Was The Week That Was''.

Joseph Heller's most famous work, ''Catch-22'' (1961), satirizes bureaucracy and the military, and is frequently cited as one of the greatest literary works of the twentieth century. Departing from traditional Hollywood farce and screwball comedy film, screwball, director and comedian Jerry Lewis used satire in his self-directed films ''The Bellboy'' (1960), ''The Errand Boy'' (1961) and ''The Patsy (1964 film), The Patsy'' (1964) to comment on celebrity and the star-making machinery of Hollywood.

The film ''Dr. Strangelove'' (1964) starring Peter Sellers was a popular satire on the Cold War.

Contemporary satire

Contemporary popular usage of the term "satire" is often very imprecise. While satire often uses caricature and parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

, by no means are all uses of these or other humorous devices satiric. Refer to the careful definition of satire that heads this article. ''The Cambridge Companion to Roman Satire'' also warns of the ambiguous nature of satire:

Satire is used on many UK television programmes, particularly popular panel shows and quiz shows such as ''Mock the Week'' (2005–ongoing) and ''Have I Got News for You'' (1990–ongoing). It is found on radio quiz shows such as ''The News Quiz'' (1977–ongoing) and ''The Now Show'' (1998–ongoing). One of the most watched UK television shows of the 1980s and early 1990s, the puppet show ''Spitting Image'' was a satire of the British Royal Family, royal family, politics, entertainment, sport and British culture of the era. Spitting Image#Evolution, Court Flunkey from ''Spitting Image'' is a caricature of James Gillray, intended as a homage to the father of political cartooning.

Created by DMA Design in 1997, satire features prominently in the British video game series ''Grand Theft Auto''. Another example is the ''Fallout (series), Fallout'' series, namely Interplay Entertainment, Interplay-developed ''Fallout (video game), Fallout: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game'' (1995). Other games utilizing satire include ''Postal (video game), Postal'' (1997),

Satire is used on many UK television programmes, particularly popular panel shows and quiz shows such as ''Mock the Week'' (2005–ongoing) and ''Have I Got News for You'' (1990–ongoing). It is found on radio quiz shows such as ''The News Quiz'' (1977–ongoing) and ''The Now Show'' (1998–ongoing). One of the most watched UK television shows of the 1980s and early 1990s, the puppet show ''Spitting Image'' was a satire of the British Royal Family, royal family, politics, entertainment, sport and British culture of the era. Spitting Image#Evolution, Court Flunkey from ''Spitting Image'' is a caricature of James Gillray, intended as a homage to the father of political cartooning.

Created by DMA Design in 1997, satire features prominently in the British video game series ''Grand Theft Auto''. Another example is the ''Fallout (series), Fallout'' series, namely Interplay Entertainment, Interplay-developed ''Fallout (video game), Fallout: A Post Nuclear Role Playing Game'' (1995). Other games utilizing satire include ''Postal (video game), Postal'' (1997),[Byron G, Townshend D (2013). ''The Gothic World''. Routledge. p. 456. . Quote: "[P]resent themselves as deliberately controversial, incorporating hyper-violent gameplay, dark social satire and conspicuous political incorrectness[.]"] ''State of Emergency (video game), State of Emergency'' (2002),[ ''Phone Story'' (2011), and ''7 Billion Humans'' (2018).

Trey Parker and Matt Stone's ''South Park'' (1997–ongoing) relies almost exclusively on satire to address issues in American culture, with episodes addressing With Apologies to Jesse Jackson, racism, The Passion of the Jew, anti-Semitism, Go God Go, militant atheism, Big Gay Al's Big Gay Boat Ride, homophobia, Eat, Pray, Queef, sexism, Rainforest Shmainforest, environmentalism, Gnomes (South Park), corporate culture, The Death Camp of Tolerance, political correctness and Red Hot Catholic Love, anti-Catholicism, among many other issues.

Satirical web series and sites include Emmy-nominated ''Honest Trailers'' (2012–), Internet phenomena-themed Encyclopedia Dramatica (2004–),][.] Uncyclopedia (2005–), self-proclaimed "America's Finest News Source" ''The Onion'' (1988–). and ''The Onion's'' conservative counterpart ''The Babylon Bee'' (2016–).